Of all BL’s quirky cars and disappointing failures, one stands above all, symbolising both those traits in the template for the modern family car.

Anyone who’s ever watched read one of my articles or watched one of my videos knows that I love an underdog. I love cars that have interesting engineering and a convoluted history. Because it’s cars like this that allow us to look at the social history of motoring. And when I hear people cry that a particular car is ‘rubbish’, or something along those lines, it makes me all the more intrigued. It’s for all those reasons that I take such an interest in the artist formerly known as British Leyland, and what better car to study the simultaneous genius and failure of that company is there than the Austin Maxi?

So, in this article, we’re going to look at the development and history of this criminally underrated and very forward-thinking car, then work out why the Maxi was so unloved in period, and as a result, how British Leyland found itself in such a deep hole in the early

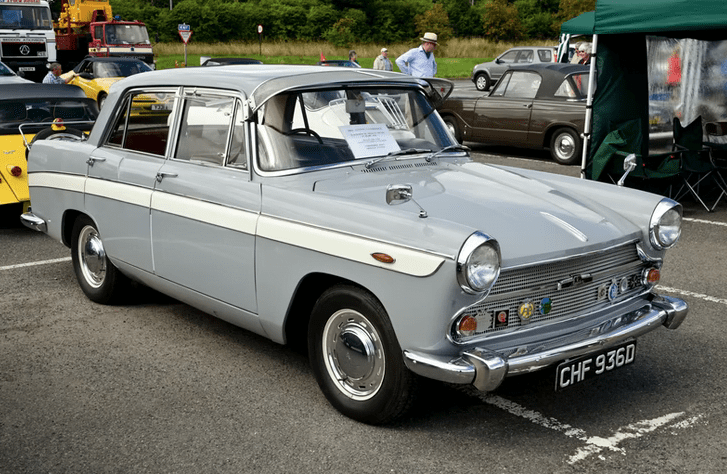

To understand why the Maxi exists, we must first travel back to BMC in the mid-1960s. The company’s existing mid-size family saloons were the Austin Cambridge and Morris Oxford, known collectively as the Farinas thanks to their Pininfarina styling. These models were launched in 1959, but very quickly began to look outdated. It wasn’t because they weren’t good cars, but because of the introduction of competitors like the Ford Cortina in 1962..

But BMC knew where the future lay in car design. They had the services of their genius engineer, Alec Issigonis, who had proved with his Mini and 1100 that transverse engines and front-wheel drive were the answer. But to complete the set, BMC needed an all-new mid-sized saloon. The car they developed and launched was the Austin and Morris 1800, or the Landcrab as it became known. But thanks to an awful lot of product drift, it was really too large to compete directly with the Cortina. And in terms of desirability, the Landcrab’s awkward styling and stance, hence the nickname, and Issigonis’ taste for minimalism meant that this car was a failure.

As a result, the Farinas remained in production, and BMC commissioned a new car that would complement the Landcrab but compete more directly with the Cortina, featuring a smaller body, smaller engines, and a much-needed dose of desirability. Work began on this new car less than a year after the Landcrab was launched, in mid-1965, an indication of just how quickly BMC had noticed a problem. The baseline for the new car was to sit on a wheelbase of 100 inches, roughly halfway between the 1100 and 1800, and two inches longer than the Mk2 Cortina, but this, almost immediately, is where it all began to go wrong.

A few sentences ago, I mentioned the product drift encountered by the Landcrab, but almost from the outset the Maxi was constrained by the existing car. In an effort to stem the haemorrhaging of money from BMC, managing director George Harriman demanded that the new car used the doors from the old car. This immediately scuppered any opportunity for the Maxi to pull itself away from the awkwardness of the Landcrab. The doors meant the wheelbase had to be extended by about 6 inches and the rake of the windscreen was pre-set before anyone had even thought about the styling. So, when the Maxi was launched in 1969, it already looked about five years old. And these doors are responsible for people even today, over 50 years on, confusing the Landcrab and the Maxi.

Landcrab and Maxi shared their doors, leading to people, even today, confusing and equating the two different cars.

Landcrab and Maxi shared their doors, leading to people, even today, confusing and equating the two different cars.

But the positive coming from this is that BMC did save a little bit of money. After all, that’s something they really needed at the time. But then they decided that the Maxi deserved an all-new engine. The new engine was known as the E-Series, and it wasn’t purely designed for the Maxi, but to replace the elderly B-Series that featured in cars including the Landcrab and MG B.

On paper, the new unit brought BMC’s engines up to date with an overhead camshaft and an all-new factory in which to produce it, but, yet again, things were about to get a little complicated. Issigonis, in a moment of insanity, dictated that instead of simply having a range of different engine sizes, the larger E-Series should instead be a straight-six. In order to fit that in with the transverse engine, front-wheel drive mantra that BMC was pursuing, the engine had to be incredibly compact, and with those two conditions in place, the E-Series began to emerge as a four-cylinder at 1.5 litres, and a six-cylinder at 2.2 litres. The Maxi was planned to only receive the four-pot E-Series, but years before its launch, the engineers began to notice that the 1500 unit wasn’t quite up to the task of being the Maxi’s only engine.

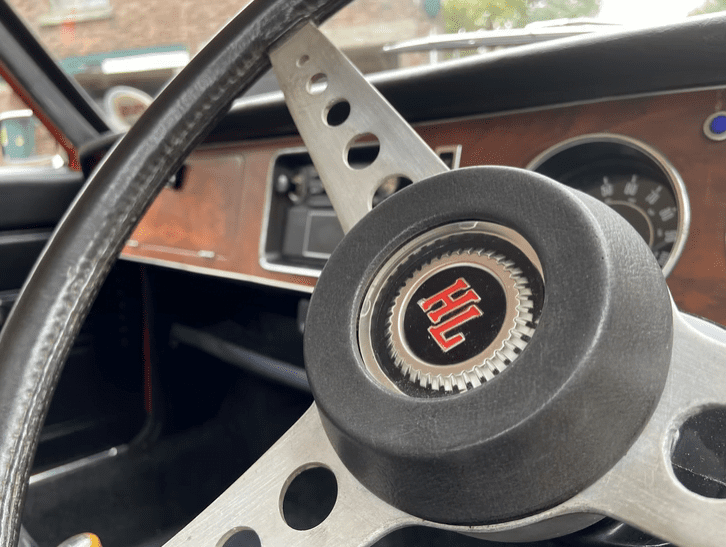

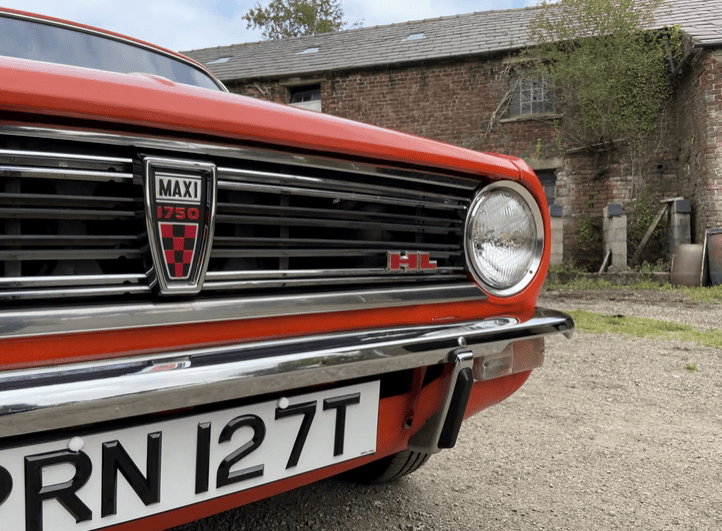

This all reeks of a company in a truly dire state, not being able to even conjure up a coherent new model or new engine range, never mind return itself to health. But the engineers dealt with the limitations, adjusting the stroke to increase the displacement to 1750cc, as we have here in this top of the range Maxi HL. That spec also includes twin HS6 SU carburettors, bringing the power output up to 91 bhp and torque to 104 lb-ft, just shy of the 2-litre Cortina.

Though the Maxi wouldn’t receive the straight-six E-Series, the common tooling did have an impact on the four-pot. In order to fit the engine transversely in other products, it prioritised a long stroke, making the engine taller, and necessitated the continuation of the famous BMC gearbox-in-sump layout. Though by this point FIAT had shown that the way forwards was mounting the gearbox on the end of the crankshaft, BMC stuck with their existing layout, and as they’d designed a new engine, a new gearbox followed suit, but despite the engineering peculiarities, this was the first factor that would put the Maxi well-ahead of the competition.

This big advance was the inclusion of a five-speed gearbox. Now for 1969, this wasn’t just a nice feature, but it was a first for a mainstream family car, and not only that, but the five-speed ‘box was standard fitment. The early 1970s saw a fair few cars launch with an extra ratio, but it took until the 1990s for most cars to come with five-speeds as standard. In fact, the Maxi was so ahead of its time in this regard that an awful lot of commentators questioned its use. They complained that five speeds were too many, or that people wouldn’t feel the need to use it. I do wonder what they’d think about modern automatics with ten-speeds, but there we are.

But there was a far bigger issue for the Maxi’s gearbox to contend with. Rather than use a long pudding-stirrer gear lever that went straight into the back of the gearbox or rods to provide a remote change, the Maxi would instead use cables to command the gears. A cable change gearbox is now the standard for a manual transmission. For decades, manufacturers have used this technique to be able to place the gear lever and the selector mechanism on the ‘box itself wherever they wish, but when the Maxi was launched, this was still novel.

While the existing rod change gears-in-sump layout was never the final word in refinement or gearchange quality, it was acceptable for its day, but combine that with an underdeveloped cable change system and it was a disaster. BMC knew before its launch that the change quality was unacceptable, but once it was launched the press confirmed their fears. The Maxi’s gearchange was appalling, and so, despite the advances, barely anybody cared.

The annoying part of this story, which is beginning to become a theme with Austin-Morris BL products, is that they knew the issues existed. In fact, the Maxi was rushed out, being launched in April 1969, following a few years of internal disagreements, stunted development, and questionable engineering solutions, and as such, nobody at BL was happy with the car as it was launched. In fact, a rather major facelift appeared only 18 months later, in October 1970. As part of that upgrade, the Maxi received a new grille, a new dashboard, and, most importantly, a rod change mechanism. The cable system was just underdeveloped, and in the intervening months, BL decided that the best cause of action was to take the easy route out, and cut their losses when it came to the car’s reputation.

The palaver with the Maxi’s gearbox severely affected that reputation, and while the rod change would never set the world alight, it is absolutely not the utter disaster that armchair commentators would have you believe. But that is proof of the importance of good press and a positive public perception. Once word was out there, no matter the alterations, the Maxi’s reputation for an awful gearchange was set in stone, but what the facelift couldn’t fully cure was the styling. The existing Landcrab had very short overhangs, and with the Maxi sharing its doors, BMC had no choice in how the Maxi’s side profile appeared. The angle of the windscreen and roofline as well as the positioning of the rear wheels were all set before anybody had started thinking.

In fact, the styling of the Maxi became a full-blown crisis. BMC knew they’d failed with the Landcrab, and in the perilous financial position they found themselves, they really couldn’t afford another ugly duckling. The car was facelifted a number of times before it ever hit the road, gaining enough attention to attract an article in The Times.

But BMC had gained the services of Roy Haynes, former design director at Ford, and he was charged with making the Maxi as presentable as possible. It’s for this reason that the Maxi shares a glaring frontal similarity with the Cortina, and this look was shared with the facelifted Mini, to go alongside each other as the Austin Mini and Austin Maxi. For me, this is the best angle of the Maxi. For 1969, this is a sharp, modern appearance, but it’s as we look beyond that it begins to tread on uneven ground.

Take the Landcrab-sourced doors. They’re doors. They’re fine. They are a little too long for a car of this size, hence the wheelbase extension and the Maxi appearing slightly stretched, but nobody is at all offended by them. The issue the stylists faced, though, was not in how to integrate the Landcrab’s doors into a smaller car, but how to integrate the Maxi’s signature design advantage – the appearance of a hatchback. The Maxi was by no means the first in this regard, as the Renault 16, for example, had been about for a few years, but this was something that no car maker in Britain had even considered in a car of this type. The task was to give the Maxi the practicality feature that would put it ahead of any other mainstream family car in Britain, without making it look as though it was an estate car. As a result, the angle of the tailgate was decided by the placement of the rear wheels and the rear doors. Nothing at all to do with a stylistic decision. Therefore, the Maxi’s style exists purely thanks to practicality and a make-do-and-mend attitude. This is reflected in the sheer size of the tailgate, which we’ll get to later, and the rear lamps. They’re triangular-shaped and designed to interfere as little as possible with the Maxi’s load carrying capabilities.

Additionally, those doors debuted in 1964. Five years before the Maxi’s launch, making it appear dated from day one. And that issue was compounded by the beauty of the Mk2 Ford Cortina, then the shift towards the curvy Coke-bottle styling of the Mk3. This contrast made the Maxi deeply uncool. It just looked old.

Combine old with awkward and we’re well along the path to a car that is ridiculed, but does this mean the Maxi is ugly? I don’t think it is. It’s certainly awkward, but looking at it from a classic perspective, it’s such a mishmash of styles that it draws my attention in. Once you understand why the decisions were made, it begins to make more and more sense as an example of utilitarian design, like the Renault 4, for example, necessitated in this case by a company that was falling to its knees. The individual marques that made up BMC, formed in 1952, joined into the even bigger party of British Leyland in 1968, and with this company beginning to sink, management did finally notice that a change of direction was necessary.

The Maxi was the beginning of a sea change at BL, as the existing Mini, 1100, and Landcrab were all badge-engineered to death. The mergers and buy-outs that led to BMC meant these three cars could be Austins, Morrises, Wolseleys, Rileys, MGs, or Vanden Plases, and this didn’t just confuse the customer, but it caused friction within the company. Those who worked at the factories once belonging to Austin or Morris felt allegiance to their marque, and even the dealers were split down those lines. This is what led to the idea that BL hated itself, and in part that was true. When it came to launching the Maxi, a decision was made that this car would only ever be an Austin.

BL’s two main volume marques, Austin and Morris, would be retained but each selling very different cars. Austins would be technologically advanced and avant-garde, like the Maxi here, while Morrises were completely the opposite. They were planned to be basic, proven transport to compete directly with the likes of Ford, though only three cars, the Austin Maxi, Morris Marina, and Austin Allegro, were developed in this mindset.

While this would eventually fall apart as BL neared collapse in 1975, it paved the way for the rationalisation that temporarily saved the company through to the 1980s, but before that could happen, one more quirk of the Leyland era would hit the way the Maxi was marketed. Following BL’s effective nationalisation, a few cars became purely Leyland products, therefore being allowed to be sold by both Austin and Morris dealers, helping that rationalisation along in the short term, even if this was to the detriment of brand recognition. The Mini, Princess, and Maxi had lost their identities, being branded purely with the Leyland plughole, hence the lack of Austin badges on this 1979 example. Additionally, despite the Maxi being considered an Austin, it was actually built at Cowley, the home of Morris, bringing with it another tiny step in integration and rationalisation.

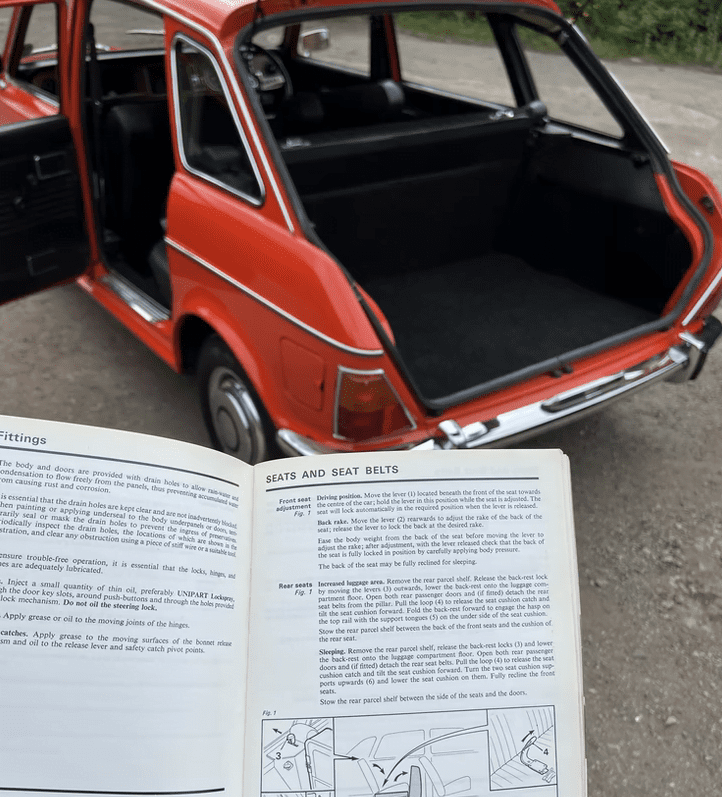

The Maxi’s marketing and public image were messy at best, and so, the way we see the Maxi’s genius is both through the mechanical layout, and its sheer brilliance when it comes to just being transport. So how practical does the fifth door actually make the Maxi? After all, everything’s available with a hatchback now, so what makes this thing so special? Well, first of all, the door is enormous. It is absolutely as large as they could engineer it, and though that does make it very heavy, there is no load lip, and if you can’t fit something through the gap, then it ain’t fitting in the boot anyway.

Taking away the parcel shelf, how BMC engineered so much space into a car that is smaller than the current Fiesta (and yes, it genuinely is) I have no idea. The leap between the saloon cars of the day, with which you had to drop things down into the boot, and the Maxi is enormous. It’s more like a van than a car, and there’s no wonder BL used the Maxi’s practicality in its marketing for years. Compared to any other car, including fellow hatchback, the Renault 16, the Maxi is miles ahead. It was at the very genesis of people in Britain switching towards hatchbacks, as other manufacturers slowly caught up through the following decade and a half. In fact, it would take the former Rootes Group until 1975, then Vauxhall and Ford until 1981 and ‘82, respectively, to follow the Maxi’s lead in offering a mid-size family car as a fully-fledged hatchback.

But we can’t talk about the boot without showing off the Maxi’s party piece, as this interior was designed to be versatile, and so, the rear seats fold to a completely flat load bay, and then all the seats recline into a bed. How many people… made use of it I do not know, but it’s a bed!

Considering then that it is smaller than a new Fiesta, you might imagine that the passengers are rather hard done by considering the amount of room dedicated to luggage, but you’d be wrong. Thanks to the Landcrab doors and that lengthened wheelbase over the original concept, it is incredibly spacious in the back. The seats are lovely and squishy and despite the black upholstery, it feels so airy thanks to the big glasshouse. That also means visibility is perfect.

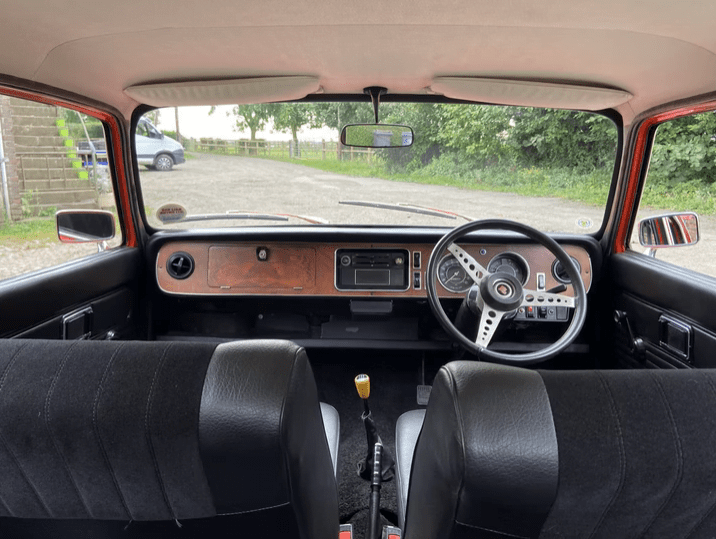

In the front, it’s much the same story, but compared to the Mini, 1100, and Landcrab, the Maxi feels so much more grown-up. As I mentioned earlier, one of the major Landcrab criticisms was how minimalist it was, and consumers felt that they were driving a cheaper car as a result. This undoubtedly upset Issigonis, but the Maxi actually got a proper dashboard. This was another thing updated in the 1970 facelift, though it was actually simplified a little. I do think it’s indicative of the Landcrab’s simplicity when this can be described as luxurious, but in comparison, it really is, though it’s all still very simple.

From a practical perspective, the Maxi was brilliant. A car that was incredibly well packaged and engineered to impress. Transverse engines, front-wheel drive and Hydrolastic suspension may not have been new for BL, but compared to the rest of the market, it was still comfortably ahead. It rode and handled brilliantly, would take any people and luggage a family could throw at it, but this is all proof that perception is more important than engineering.

The Austin Maxi was never the car it should have been, but there is absolutely no doubt that it is a work of pure genius. Had it been designed and produced by a company with stable foundations, it would have been nothing but a world-beater. But unfortunately, it had British Leyland behind it, and so, it stumbled its way through development and life never having found its potential. This is one of the great ‘might-have-beens’, had it not been stunted by both its parent company and the arrogance of Alec Issigonis.

As I said a few weeks ago with the Mini, Issigonis was a genius. There’s no other word for him. But no genius gets away with it forever, and as time moved along, Issigonis’ ideas were plagued by both BL and a world that was moving on. The Maxi would be his last car. Despite his knighthood in 1969, he was pushed out of BL to become a consultant, working on ingenious economy cars and straight-six engines for the remainder of his life.

Despite the relative failure of the Landcrab and Maxi, Issigonis produced some of Britain’s best-selling cars of all time. The Morris Minor brought Britain out of wartime. The Mini became the most influential car of all time, and the Austin-Morris 1100 followed that theme, being the best-selling car in Britain for the best part of a decade.

At the Maxi’s launch, head of the new BL, Donald Stokes, proclaimed that “we believe that it will create the same kind of revolution in the field of middle-class family motor cars as did the Mini in the realm of small cars”. And despite the underwhelm at the car’s launch, he was right. It may have taken decades, but almost every car ended up having a transverse engine, front-wheel drive, a hatchback, and a five-speed, cable operated gearbox.

The Austin Maxi was never the finest car. It suffered the typical BL fates of niggling design issues, poor build quality, and a truly dreadful public image, but at the same time, it was the trendsetter for what the family car became. And so, what better a car to describe British Leyland than the Maxi, a perfect blend of genius and failure, encapsulating why I love that company and the paradox in the work of the great Alec Issigonis.