Biddle

The Biddle Motor Car Company manufactured luxury automobiles in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania from 1915 to 1922.

"Information, rather than Persuasive Sales Talk" was the advertising slogan of the company, which was noted for its conservative advertising. The company produced six models, with the heaviest weighing 2,950 pounds with a 48 bhp (36 kW) four-cylinder engine being sold for $3475.

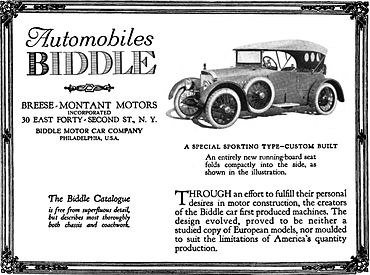

The company was incorporated in October 1915 and presented finished automobiles at the Philadelphia Auto Show in January 1916. It was namesake of the Biddle family, although R. Ralston Biddle did not seem to have a major role beyond lending the name. Car was an assembled car manufactured in Philadelphia. The first bodies were believed to be from the Fleetwood body company in Fleetwood, Pennsylvania. The first cars were equipped with Buda four-cylinder engines, 33⁄4 Bore by 51⁄8 stroke and Warner 3-speed transmissions. Some models featured Rudge-Whitworth wire wheels. The bodies were styled in the European tradition. Biddle stood out with V-shaped radiators, angular or cycle fenders, step plates instead of the usual running boards, and dual side-mounted wire wheels when that concept was still strictly European.

A Biddle advertisement appearing in Life Magazine in 1917 confirms that the car was "assembled" from parts produced by others, including a top-quality Duesenberg motor, and that it reflected European styling. The roadster shown in the ad closely resembles a contemporaneous Mercedes Benz sport model, with its deeply V-ed radiator, cycle fenders, wire wheels and step plates. From its dramatic prow, the long hood-line sweeps back to a raked windshield spanning an aeronautical cowl, then drops to the rakish line of its cut-down doors and finally flows into a streamlined tail.

The car is pictured in the unacknowledged drawing standing at the foot of a long drive winding down from a Colonial-style golf club through a manicured lawn. The drawing is heavily influenced by Japanese printmaking in its linearity, stark use of light and shade, and abstract composition. The sophisticated imagery of the advertisement is complemented by an elegantly lettered text, headed by the haiku, ‘Automobiles Biddle Speed’ and the following evocative declaration:

The thrills of speed with perfect control are his who drives the Biddle car equipped with Duesenberg Motor. Security and comfort are also his – for the character of construction assures them.

Both the spare, poetic copy and the oriental minimalism of the image clearly represent the high standard of design and equally high aspirations of the company for its customer base. Biddle was one of more than 2000 car makers, located all over the USA in the first quarter of the twentieth century, who failed to survive the intensifying pressures of mass-production and national distribution in the late teens and the intense competition imposed by massive corporate consolidations in the early 1920s.

When Biddle Met Duesenberg

By STEVEN UJIFUSA

The early twentieth century was the Wild West of the American automotive era. Hundreds of manufacturers sprung up in cities and towns across the nation. Most failed within a year, usually after producing only a dozen machines. In 1915, Philadelphia auto enthusiasts opened their magazines to see advertisements trumpeting a new American luxury car. The car looked suspiciously like a Mercedes-Benz: a sharp, V-shaped radiator; a low-slung chassis; wire-spoked wheels; curved bicycle-style fenders. Unlike bulky, lumbering American luxury cars in its price-range — such as Packard and Pierce-Arrow — the Biddle was nimble and sporty looking, built on a mere 120 inch wheel base, with step plates instead of running boards.

The company claimed that the Biddle was “neither a studied copy of European models, nor moulded to suit the limitations of American’s quantity production.”

The namesake of the car was one Robert Ralston Biddle, who apparently loved cars but contributed little else to the machine’s development other than his storied last name of Second Bank of the United States fame. According to the 1910 Philadelphia Social Register, Biddle lived with Misses Catherine and Sarah Biddle (presumably his sisters) in a brick townhouse at 1326 Spruce Street.

Philadelphia’s car was attractive but hardly revolutionary. In the judgement of automotive historian Beverley Ray Kimes, “what the Biddle did best was look good.” The Biddle was a so-called “assembled” car. Rather than making their parts from scratch like Ford or General Motors, the company purchased pre-assembled engines, axles, and other components from outside suppliers and then assembled them into an attractive, sleek package. Not that the Biddle was a slipshod job. Its components were all of the highest quality. The car’s price started at $1,650 for the chassis alone, and a variety of custom Fleetwood bodies could be ordered (limousine, town car, roadster, touring car) for an additional $2,000 to $4,000. In today’s money, a well-outfitted Biddle would cost about $65,000. By comparison, a Ford Model T cost about $850, or about $18,000 today.

Yet what really made the Biddle stand-out was its four-cylinder engine, manufactured by the Duesenberg brothers of Indianapolis and able to crank out 100 horsepower, five times more than Ford’s Tin Lizzie. Fred and August Duesenberg were American originals. They immigrated to America from Germany with their widowed mother in 1885, and grew up tinkering with machinery on the family farm in Iowa. After racing bicycles for a few years, the brothers started a company that manufactured race car and marine engines. Fred proved to be a mechanical genius, and by 1914 Duesenberg-powered cars were garnering trophies at the Indianapolis 500.

The success of the four-cylinder Duesenberg racing engine attracted the attention of Arthur Maris, president of Biddle, and of Charles Fry, the company engineer. The year after production started, Biddle removed the original Buda powerplant from its cars and installed the more powerful Duesenberg one instead.

Unfortunately, Biddle arrived on the scene at exactly the wrong time. America’s entry into World War I in 1917 squashed demand for luxury cars, and the brief, post-war recession that followed made matters even worse. The automotive industry was also undergoing structural changes and consolidation. President Alfred Sloan of General Motors purchased a clutch of independent companies (Chevrolet, Buick, Oldsmobile, and Cadillac) and integrated them into a consortium that could corner all segments of the market. General Motors also purchased suppliers and integrated their products into an in-house supply chain. The company purchased Fleetwood, for example, so that the distinguished “carriage trade” body maker could supply custom bodies for the prestigious Cadillac marque, not Biddle and other smaller luxury makes. In the meantime, Henry Ford perfected his assembly line, which could churn out dozens of cars an hour. As a result, the price of a Model T dropped from $850 in 1908 to a mere $260 by the early 1920s.

In this new economic landscape, there was no room for niche companies like Biddle to compete. At its peak in the late 1910s, Biddle was only building 500 cars a year at its expanded Frankford Avenue plant. Philadelphia’s Biddle Motor Car Company closed its doors in 1922, just as the economy began to take off and America, as F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote, entered “the greatest, gaudiest spree in history.” Company president Maris went to Wilmington, Delaware to launch a new car company backed by E. Paul du Pont. Like the Biddle, the du Pont was also an “assembled car” with a fancy name and glamorous coachwork, but relatively conventional mechanical guts.

Yet Biddle’s choice of engine supported a company that would become the biggest automotive star of the Roaring Twenties. In early 1929, Fred Duesenberg and his partner E.L. Cord unveiled the Duesenberg Model J: the fastest, most powerful, and costliest production car in the world. Under the hood was a Duesenberg-designed 6.9 liter straight eight, able to develop 265 horsepower — twice as powerful as the closest European competitor. It had so much torque that it could supposedly do 60 miles per hour in second gear, at a time when a good car topped out at that speed.

Sadly, Fred Duesenberg was one of those unfortunate geniuses killed by his own creation. He died in 1932 after flipping a supercharged Model J on a slick road near Johnstown, Pennsylvania.

The site of the Biddle Motor Car plant at 1210 Frankford Avenue is now occupied by the Frankford Hall beer garden.

Little is known about the fate of Robert Ralston Biddle.

In the passenger seat of a 1929 Duesenberg Model J. The car’s straight eight engine developed 265 horsepower, or 325 in the supercharged version, and able to propel the three ton car at up to 115 miles per hour. A much smaller, four-cylinder Duesenberg engine powered the Biddle during its 1917-1921 production run. A well-equipped, coach-built Duesenberg sedan sold for about $12,000 ($8,500 for the chassis alone), or about $170,000 today.

No models found