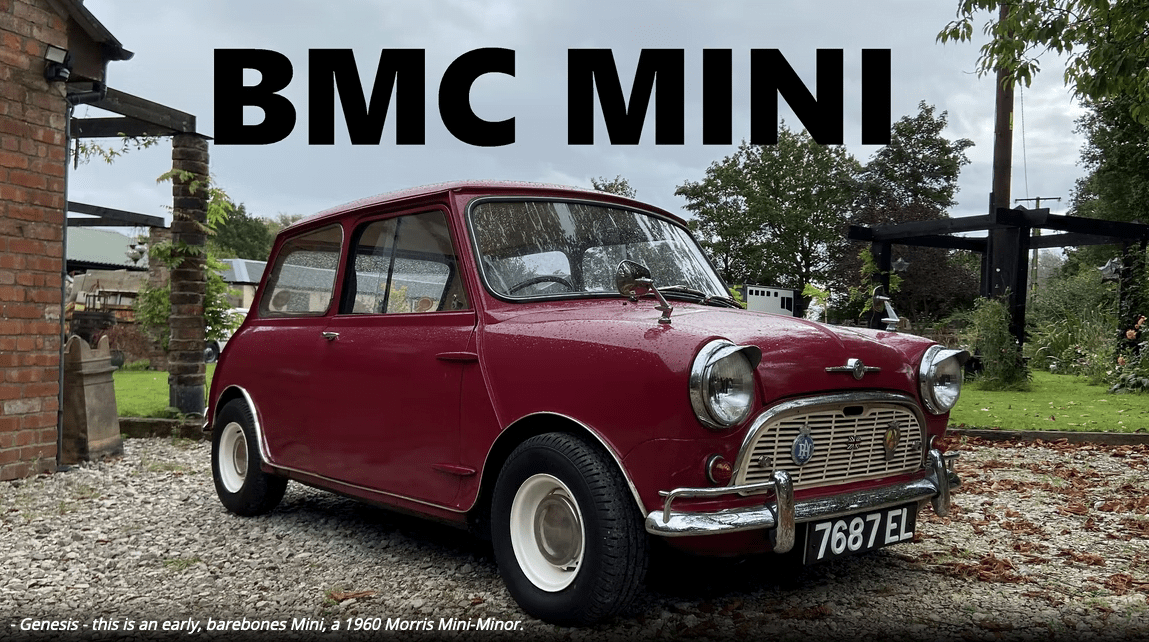

With its transverse engine, unusual shape, and tiny footprint, Sir Alec Issigonis’ Mini set the template for the entire modern motor industry.

Of all the cars I’m fortunate enough to photograph and video, none have the power to make me as happy and childlike as what has always been my favourite car of all time. What else could it be, but a Mini, and the one we have here is a very early one. So in this article, we’re going to go deep into the development and engineering of the Mini, then begin to understand how this sweet little economy car became such an icon and one of the most important cars in history.

The format the Mini pioneered has become the basis of the modern motor industry, so before we can even think about looking at the Suez crisis and Alec Issigonis, we must first understand what the average small car looked like before the Mini.

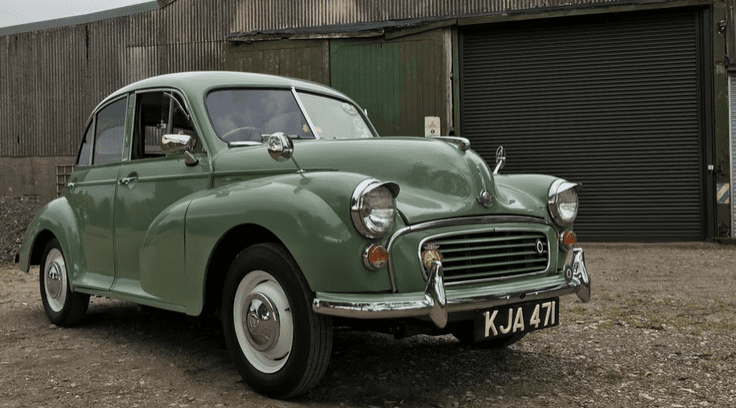

In the decade after the Second World War, car ownership was still relatively low, and the most common small cars were things like the Austin A30 and Morris Minor. But as the 1950s progressed, car ownership was picking up as rationing ended and Butskellism appeared to be working.

BMC’s Morris Minor – the Mini’s older sister.

These political conditions are important, as they are the only reason the Mini exists. In 1955, Winston Churchill resigned as Conservative leader and Prime Minister, to be replaced by his Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden. Eden’s Conservatives won the 1955 General Election, but disaster was just around the corner. While Eden was Foreign Secretary, revolution broke out in Egypt, driving the British out and eventually leaving Gamal Abdel Nasser in charge.

Colonel Nasser, President of Egypt.

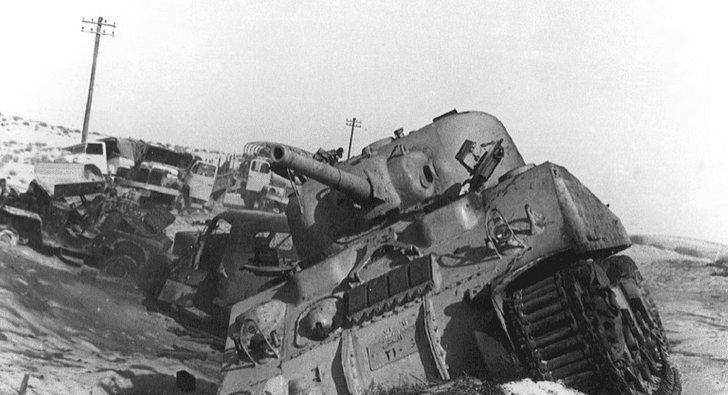

As we know from more recent history, the Suez Canal is a vital artery when it comes to trade, allowing ships to cut through Egypt rather than having to travel around the perimeter of Africa. And in 1956 this was no different. The ownership of the canal was private, split between French and British interests, but Colonel Nasser was not on board with foreign control over an Egyptian asset. As a result, he declared that the Suez Canal Company was to be nationalised, and this greatly angered the British and French, leading them both to essentially invade the region with the help of Israel.

Sinai.

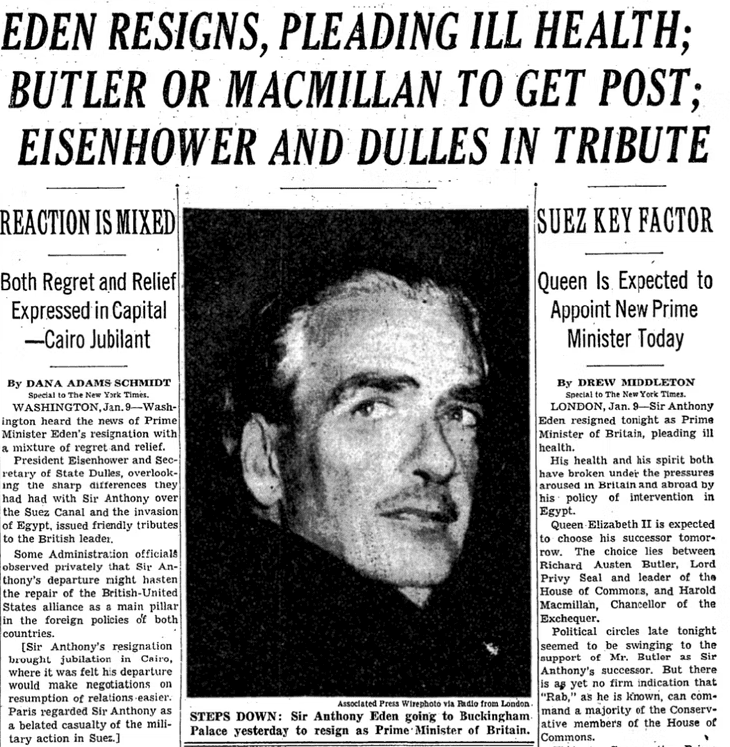

In 1956, however, they lacked the political clout to see their invasion through. They were all still reeling from the Second World War, and the United States, who had become the superpower, told the three nations to go home. The former Foreign Secretary, Eden, had just committed a foreign policy calamity, and he resigned in disgrace after less than two years as Prime Minister, to be succeeded by his Chancellor of the Exchequer, Harold Macmillan.

The New York Times, 9th January 1957.

The consequences of Britain’s last attempt to retain some global power hit the motor industry hard. Oil shortages started to take their toll and in December 1956, the government had to introduce fuel rationing. Overnight, the demand for cars dried up as people couldn’t afford to fuel their vehicles or didn’t have the rations available to them. The only segment of the industry in which demand increased was for microcars. People were suddenly clambering over each other to get their hands on Isettas, Messerschmitts, and Bond Minicars.

The Isetta – probably the most famous of the ‘bubble cars’.

A man named Leonard Lord was then President of BMC, Britain’s largest car company and the product of a merger between Austin and Morris. At Lord’s disposal was the genius of Alec Issigonis, who the decade before had designed the Morris Minor. Lord made his feelings towards these ‘bubble cars’ rather clear. “God damn these bloody awful bubble cars. We must drive them off the streets by designing a proper small car.” And so, Issigonis did.

The Mini, therefore, was not designed to replace the Austin A30 or compete with Citroen’s 2CV and the Volkswagen, but provide a tiny car that would enable those driving bubble cars to get into something that didn’t have a motorcycle engine and that wasn’t built from lollipop sticks. The closest comparison, then, is to the FIAT 600 and 500, but the Mini was radical in a way the Italians weren’t.

Issigonis and his small team of engineers wanted the new car, then known as ADO15, to absolutely maximise its practicality from an incredibly small footprint. Now there are many cars out there that are indeed smaller than a Mini. It wouldn’t have met the dimensions to be a Kei Car in Japan, for example, but ADO15 had to seat four people and take their luggage, and by that I do not mean children. Two adults had to be comfortable in the back. So this little team had their work cut out to fit a four-cylinder engine, four adults, and a proper boot into a 10 ft length and a width of 4 ft 7.

10 feet of Mini. A measure plenty of people will tell you is the only acceptable length for a Mini.

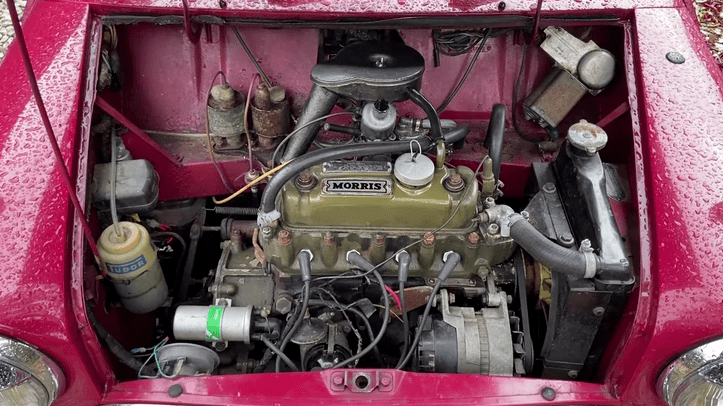

Issigonis had the engineering principles the Mini would utilise in his head for decades, but it took a project of this ambition for them all to be fleshed out. The most famous element is found under the bonnet. The vast majority of cars from this era, along with everything designed by BMC, was front-engine, rear-drive, with the engine mounted longitudinally under the bonnet. This was simple and well-proven, but impractical. It takes up a lot of space to have an engine, gearbox, propshaft, and rear axle, and the Mini aimed to avoid this level of wastage.

An alternative is to have an engine with fewer cylinders or to mount the engine at the back. But neither of these choices left Issigonis feeling confident. Front-wheel drive had the promise of more predictable handling and better roadholding, so that was the avenue ADO15 would take. The solution was to mount the engine transversely, but that left Issigonis’ team with another set of challenges.

The first and foremost of these was the gearbox. The initial plan was to mount it on the end of the crankshaft, exactly as you’d see in a rear-drive car or a modern front-drive car. But in the width permitted, Issigonis decided they couldn’t retain enough steering lock, so the gearbox was instead placed underneath the engine, sharing its oil in the sump. The drive would be dropped down to the ‘box through a set of gears, and this arrangement allowed the drive to exit the gearbox from the centre of the car, meaning equal length driveshafts and therefore, theoretically, no torque steer.

The second, most obvious component to face a challenge was the radiator. In a longitudinal setup, this would of course be at the front of the car, with the fan pulling air through the grille, cooling the engine. However, in 1959, BMC couldn’t, or wouldn’t, employ an electrically driven cooling fan, so the radiator had to remain at the front of the engine, or at the side of the Mini’s engine bay, so that the fan could act on it. The fan instead pulls the air through the front grille and into what was the back of the radiator, out into the wheel arch.

The engine BMC decided to use was their existing A-Series, the powerplant that had also propelled the Austin A30 and Morris Minor, but in the Mini, it began to cement its legendary status. This tiny, overhead-valve, Siamese port engine with a little SU carburettor perched above may appear on paper to be exceptionally unexceptional.

In this form, it displaces 848cc, producing 34 bhp and 44 lb-ft of torque. But the A-Series is very tuneable, and while Minis eventually moved away from this tiny capacity, thanks to the car’s feathery kerb weight, any A-Series could pull the Mini along incredibly well. It’s the strength, economy, and willing torque the A-Series produces that kept it a staple of the British motor industry, and that’s without even mentioning the noise the A-Series with its gearbox in sump made. That whine and grumble were the soundtrack of Britain from the 50s through to the 90s. And there’s a very good reason why these engines have cropped up absolutely everywhere, and continue to, nearly 70 years after its introduction. The A-Series is a vital component in the Mini’s character, and as we’ll discuss in a future article, was a critical component in the car’s transformation into an icon.

But even this pre-existing element of the Mini was altered between the prototype stage and the car’s launch. The prototypes had a 948cc displacement, but considering the era and the market the Mini was aimed at, the fact that some prototypes had been clocked at over 90 mph, forced BMC to nerf the performance by reducing the stroke, bringing the engine down to the final 848cc.

Some of those prototypes also had their A-Series turned the other way, with the distributor at the back and carburettor at the front, but BMC found an issue with that, though its still unknown the exact reason. The official reason was that the carburettor would ice up, leaving you with no fuel, and therefore no starting, but John Cooper, of all people, said this was rubbish. He said that the real reason was that prototype Minis were mashing their synchromesh even more than the production ones did. Now, Cooper wasn’t around for the development of the Mini, but judging by how these BMC gearbox in sump systems love to knacker a synchromesh anyway, he’s probably right. The eventual effect of this setup, however, is that all the Mini’s ignition components were now right in the firing line for the great British weather to wreak their havoc on.

But the end result was an incredible increase in the practicality of the car. No longer was a significant portion of the car’s footprint dedicated to the engine, but instead to the passengers. Such a leap it was, that virtually every car today carries this basic layout.

Now we’re getting towards the road we can talk suspension, because BMC weren’t about to stop innovating. The Mini has independent suspension all-round, something we still don’t see in all modern cars, but the springs are what we’re interested in. Coils were considered too bulky and leaves, well, the less said the better. The Mini instead uses a system developed by Alex Moulton, whereby little rubber cones act as the springs. Using rubber means a variable spring rate, and standard shock absorbers are used alongside them. But the biggest advantage is yet again in the packaging. These cones are tiny and at the rear, they’re even mounted horizontally to save intrusion into the boot.

While this setup may have made the Mini a rather harsh ride, it pushed it head and shoulders above almost all else when it came to sheer cornering ability. And it’s arguably this fact that encouraged BMC to take the Mini into motorsport, enhancing its public image and the car’s widespread popularity as a tiny performance machine, but as with the A-Series, that’s something we’ll be exploring in a future article.

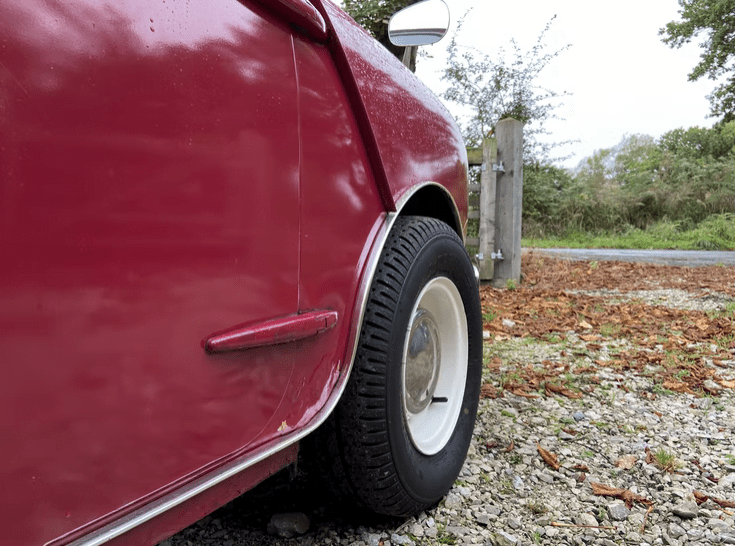

The innovations just keep coming, even down to the wheels themselves. Most cars of the time had rather large wheels, around 16 inches, but for a car so small. This just wouldn’t cut it. So BMC got Dunlop to develop them some tyres for a 10-inch rim. And that is the perfect size for a Mini. The advantage of a small wheel is a small tyre diameter, and with that comes a small wheel arch, and with that comes, you guessed it, more space for people.

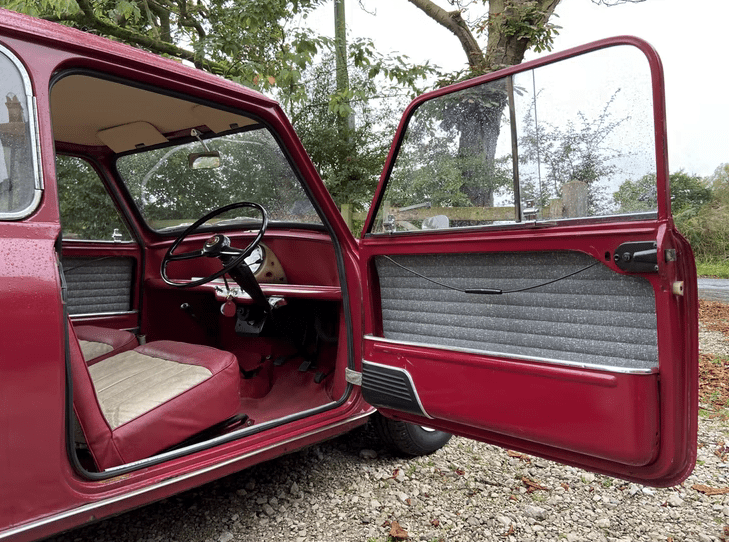

Along with packaging the car so well and using an engine as economical as the A-Series, Issigonis’ team paid an enormous amount of attention to trimming weight out of every possible part of the car. Ignore all ideas of crash safety right now. This is 1959. And take the doors as an example of that weight saving. The frames are wafer-thin, the hinges are external, and the only things separating the driver from the exterior are a single door skin and a bit of fabric. Even the door latches are simple. They’re exactly the style you’d find on a door at home.

The windows join in too. They slide across rather than roll down, and all these little touches come together to a kerb weight of 587 kg. I could cradle this car under my arm it’s so light.

But moving away from the weight and back towards practicality, these measures cultivate an interior like no other car. Internally, Minis are as big as you would ever need. There is so much room inside that you would feel comfortable living in a Mini.

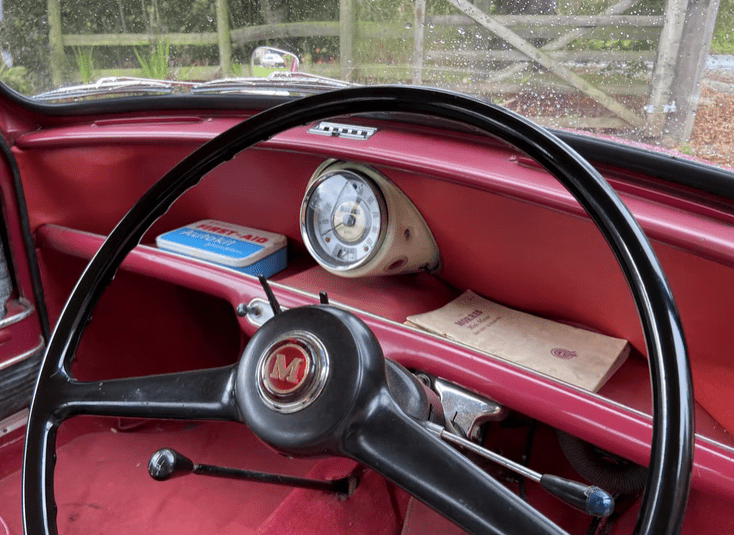

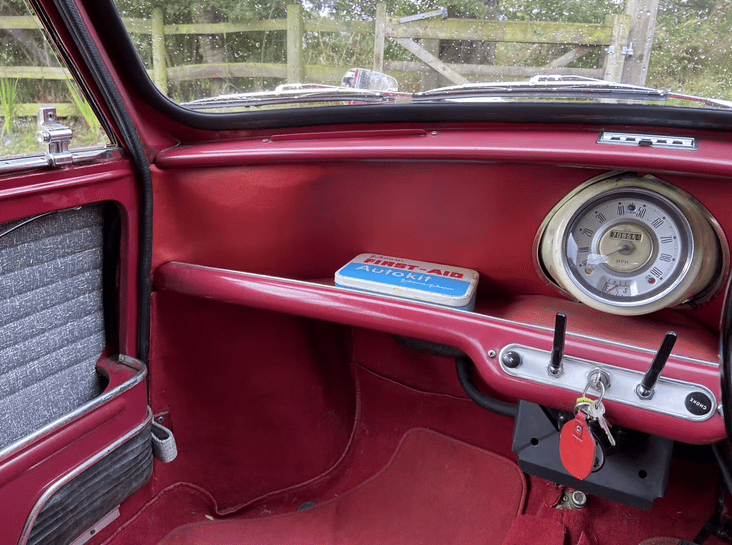

Just take the immediate view here. There is no proper dashboard. That would just take up space. So the bulkhead is just lined in fabric and this lower rail forms the support for the steering column and a shelf big enough to all of Boris Johnson’s (known) children. Photos and videos of Minis play a perspective trick on you, as you cannot begin to understand just how roomy this car is until you actually sit in one. The distance between my knees and the dashboard is larger than in anything else and that shelf really is huge. That’s a a full first aid kit nestled within. It is astonishing. Along those same lines, the door bins are fit for a bottle of wine and they extend all the way from front to back. The companion boxes in the rear are even larger.

All the space is partially thanks to the complete lack of equipment. Minis have only four features that aren’t absolutely necessary, and they are all thanks, yet again to Alec Issigonis. He was a chain smoker, so this car has four ashtrays. One for each passenger. Four ashtrays. That’s insane. There is one between the two front seats, another in the upper dash rail, and one at the front of each companion box.

That may make no sense, but the rest absolutely does. The main feature of the Mini’s interior and the one element carried over into the modern age is the single central instrument. This means that it doesn’t need to be swapped over between left- and right-hand drive but it also breaks up the vastness of this empty space. Below the speedometer is a simple row of switches containing nearly every auxiliary control.

It’s in the driving controls that things begin to look a little more agricultural, as the steering wheel juts out at an incredibly odd angle, very nearly like a bus. And that’s a by-product of making the car as small as possible. You are pushed as close to the steering rack as possible, and so, this angle presents itself, and they weren’t about to add a universal joint into the column. This is 1959 we’re talking about. Similarly, the pedals are microscopic and are tucked in around the steering column. The gear lever too is out of the ordinary, known as the ‘magic wand’ and aiming straight into the back of the sump mounted gearbox, just for ultimate simplicity.

Folding into the back of a Mini isn’t the chore you may expect it to be. There is perfectly enough room for me to sit alongside someone else in the back. No knees around ears. The Mini is just designed perfectly. What’s more. There’s even space in the boot. Now, it’s not enormous, and the hatchback hadn’t really been invented, so the Mini is a proper saloon car, though the door folds down. But when the boot is open, the number plate hinges down so you can drive along with larger loads.

When people describe Minis as TARDIS-like. They really aren’t kidding. How BMC made this car so practical I do not know. But it’s a serious feat of engineering that this 10 ft long car has more cabin space than many an executive saloon car.

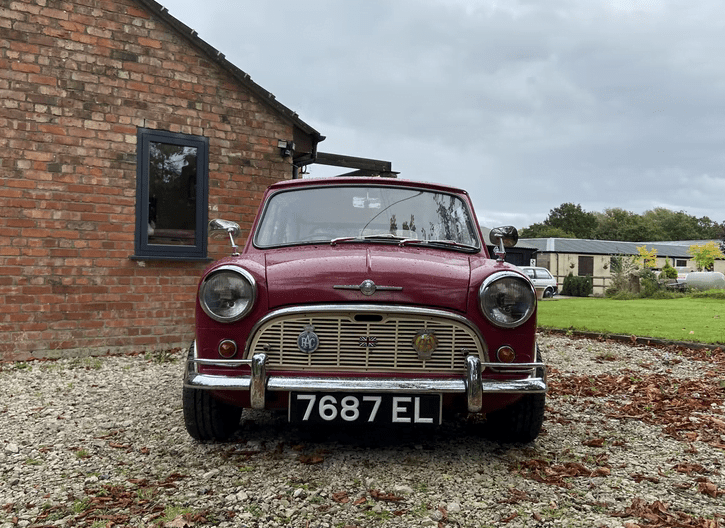

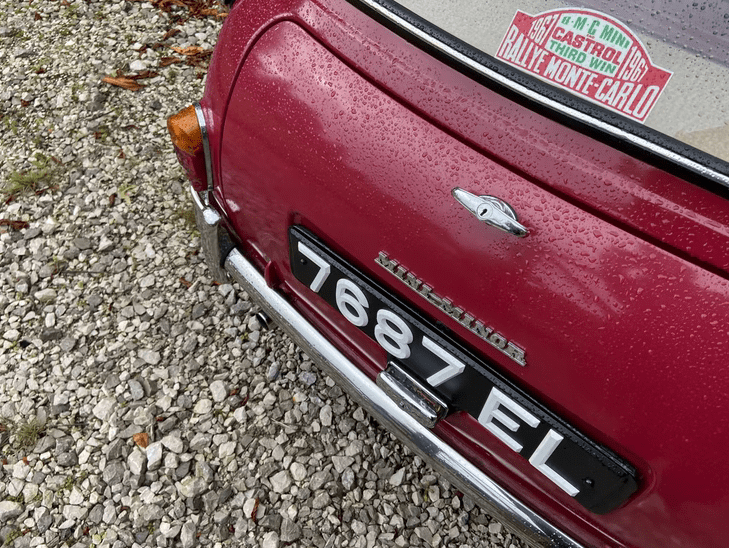

And in those tiny dimensions, Issigonis managed to chisel out an utterly timeless shape. The man was never a well-regarded stylist, only an engineer with a fetish for simplicity, so every component is small, simple, and practical. In fact, the original prototypes carried a pressed metal grille that was considered too austere by BMC management, as Issigonis was told to “jazz it up a bit”. In keeping it seems with that attitude, this example has received a few modifications over its sixty-one-year life. It has these small chrome eyelids, proper wing mirrors, and wheels from a Cooper S, but that’s pretty normal. Minis were built to be modified.

It’s with this taste for minimalism though that the shape he fleshed out became so identifiable. Nothing that was around in 1959 could be confused for a Mini, and with the characterful face the car carries, managed to slowly find its way into people’s hearts. But it was all in the interests of practicality. It’s a box with four wheels pushed as far as possible into the corners, both for better practicality and better handling.

It may seem an alien thought to all of us today, but even the style of the Mini was radical. It was so small and stumpy that people didn’t know what to make of it. Some commentators even called it ugly, but how could you do that to a Mini? The views of the time are summed up best in an article from 1961 in Motors and Motoring. The Mini has “caused a great deal of controversy and probably more interest than any other car in recent years. The design of these remarkable little vehicles broke away completely from the established conception of what a car should look like and how it should be laid out mechanically”.

At the Mini’s launch, it was known by two names, either the Austin Seven or the Morris Mini-Minor. The badge engineering of these models is useless, as they’re identical other than the grilles, badging, and minor trim, but thanks to the love directed at this little car, that was very quickly simplified to simply being the Mini. And though the Austin and Morris were later joined by a Wolseley and Riley, it took only ten years for the company that became British Leyland to realise the recognition the Mini had, and to allow it to live as its own brand.

So this car, at its launch, was £496 19s. That number may not mean an awful lot to anyone today, but it was less than the Austin A35, that ceased production at the Mini’s launch. It was £28 cheaper than a FIAT 500. It was £68 cheaper than a 2CV. It was £92 cheaper than a Ford Anglia for heaven’s sake. The Mini was better engineered, faster, handled better, and was more practical than any of those cars. Why you’d have chosen an Anglia over a Mini in 1959 I do not know, but it did take the public a bit of time to come around to the idea of minimalism. People couldn’t get their heads around the fact that this little box could fit within it a whole family, and I’d expect as well that there was a bit of the ‘bigger is better’ mantra going on. But once people did catch on to the Mini, that was it. During one month in 1960, almost 1 in 5 cars sold in Britain were Minis. Within seventeen years, they’d built four million of the things.

Surely then, this little car brought some proper success to its manufacturer? Well. No. BMC was, in almost every way a backwards company. The merger between Austin and Morris took place because both companies were facing difficulties, and the level of incompetence within led to BMC losing about £30 on every Mini they sold, at least at the beginning. That 4 million figure isn’t actually all that impressive, taken at face value. But it’s only with nuance and circumstance that we see its power. These sales were all despite BMC’s catastrophic fall to bankruptcy, rampant industrial action, iffy build quality, and an ever-declining export market. The basic car was so good that despite no replacement on the horizon, very limited investment, and an increasingly dodgy image, the company that became British Leyland relied almost completely on the Mini, and for twenty years, it remained one of Britain’s best-selling cars.

In the March of 1957, ADO15 existed only as a sketch on the back of a fag packet, but only four months later they had a running prototype, and within 25 months they had a production car. For an engineering effort of this magnitude to hit the roads in that amount of time is unheard of. The effort that went into making the Mini a reality is admirable, and it’s unsurprising in the circumstances that there were a number of teething troubles. But in April 1959, the first Minis rolled out of Longbridge and Cowley, starting a legacy that remains rich over 60 years later.

It didn’t take long for the motoring press to hail the Mini as the future, such was its tenacity on the road, charm and immense character. We all know that the Mini is one of the all-time greats, for both its design ingenuity and the grin-inducing handling that won it so many motorsports triumphs. But that story will be coming soon. For now, this is among the first Minis. As pure as Issigonis wanted it to be and as cute as it would ever be.

For Alec Issigonis, this was his finest moment. This car is how the man is remembered. For all the turmoil of his early life, and his status as a refugee at 15-years-old, then moving to England in the early 1920s, Issigonis is responsible for some of the most interesting, quirkiest, and successful British cars to ever exist.

Sir Alec Issigonis. He never designed anything exotic, but he is undoubtedly the most important car designer Britain has ever had.

But it’s his attitude towards his designs that endears him so much to me. The Mini rolled out of the factory at 10 ft and a quarter of an inch long. And it’s been said by John Sheppard, who was part of the Mini team, that this really annoyed Issigonis. That’s telling. The man who was single-minded enough to get this car launched as pure as it was, and therefore as loveable and successful as it was, was the same man who saw that single-mindedness overtake sense. Issigonis was pushed out of his position in 1969 thanks to this attitude. The man was undoubtedly a genius. But geniuses don’t always win.

If you enjoyed this article, then please do consider checking out my YouTube channel, Twin-Cam where I have a more in-depth video version.